No products in the cart.

General

Rosewood a Traditional Tone Wood Choice

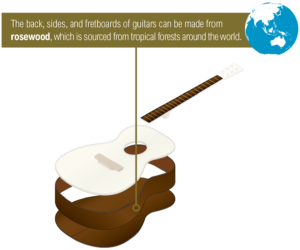

This 6th and final installment on tone woods and their sustainability within an ever growing consumer demand is about rosewood, one of the most expensive tonewood varieties. Rosewood has a lot to live up to with its smooth, warm tone and complex harmonic overtones. Visually, Rosewood is typically dark, chocolate brown in color, with a widely banded dark grain, and is generally used as a material for the back and sides of a guitar body.

Combined with a Spruce top, Rosewood provides an incredibly balanced and versatile palette of tones.

The most sought-after variety, Brazilian Rosewood, Dalbergia nigra, has become scarce and expensive in recent times, due to severe trade restrictions (embargo and CITES), scarcity and demand. The most widely used rosewood used now is east Indian Rosewood, often paired with a spruce top for steel string guitars and with spruce or cedar for classical guitars. In general terms it can be said that Indian Rosewood projects warm, but singing harmonics, while Brazilian Rosewood has a slightly brighter, less complex tone, with a defined low-end

Tonewood choices vary greatly among different instrument types. Guitar makers generally favor quartersawn wood because it provides added stiffness and dimensional stability. Soft woods, like spruce, may be split rather than sawn into boards so the board surface follows the grain as much as possible, thus limiting run-out. For most applications, wood must be dried before use, either in air or kilns. Some luthiers prefer further seasoning for several years. Some guitar manufacturers rarefy the wood, a drying method that mimics the natural aging process of tonewoods. Torrefaction also is used but often changes the cosmetic properties of the wood.

Stringed instruments have existed for thousands of years, but what we think of as a modern guitar was only born in the mid-19th century. The guitar continues to develop as an instrument today along with advancements in new technologies and production techniques. Despite its short history, though, tradition governs the industry. Most guitars adhere very closely to the same formula. This standard governs the design and sound of the instrument, but also guides the selection of wood species. Firmly entrenched in this tradition is one of the finest and most demanded woods for the back and sides of guitars: rosewood.

The industry standard—and unattainable

Rosewoods belong to the Dalbergia genus and grow in tropical forests and grasslands around the world. They are beautifully colored and according to insiders lend a fantastic resonance and richness to guitars. Unfortunately, they are also some of the most endangered trees on earth, and are at the center of illegal logging operations from Belize to Madagascar and Thailand. Rosewood accounts for 35 percent of global wildlife trafficking (nearly double that of elephants for ivory).

Rosewoods belong to the Dalbergia genus and grow in tropical forests and grasslands around the world. They are beautifully colored and according to insiders lend a fantastic resonance and richness to guitars. Unfortunately, they are also some of the most endangered trees on earth, and are at the center of illegal logging operations from Belize to Madagascar and Thailand. Rosewood accounts for 35 percent of global wildlife trafficking (nearly double that of elephants for ivory).

The traditional wood on old guitars was Brazilian rosewood (Dalbergia nigra), which is often called the “holy grail of tonewoods.” Unfortunately, it has been so overharvested that Brazil banned its export in the late 1960s, and it was protected by Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) in 1992. In response to the trade restrictions on Brazilian rosewood, guitar manufacturers chased the prized hardwood elsewhere. Many guitar manufacturers sourced rosewoods from Madagascar until Gibson Guitars was raided by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 2009 for violation of the Lacey Act with ebony wood from Madagascar. This brought the reality of Madagascar’s illegal logging crisis home for many guitar manufacturers. Today, the rosewood on guitars is by-and-large Indian rosewood (Dalbergia latifolia) that is sold by a handful of companies at state-sponsored auctions. The trees are grown as shade trees on coffee, tea, and ginger plantations and are largely government managed.

To be clear, very little of the rosewood cut in the world goes towards guitars. Most is destined for China to be used in luxury furniture. But any industry involved with rosewood today is faced with the difficult task of ensuring its legality and complying with increasingly strict international regulation.

Around the world, impoverished people, enticed by the demand, are illegally cutting valuable rosewood trees to earn a few dollars, while massive amounts of money go to timber mafias and organized crime. Given the extremely high amount of rosewood that is illegally harvested, it is very difficult to prevent illegal timber from sneaking into the supply chain. Over 75 species of rosewood are commercially traded, and species-level identification is nearly impossible, even by experts. Shipments often have false documents and illegal loggers have taken full advantage of the difficulties facing enforcement officials.

A new era for Rosewood

At the 17th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties of CITES, it was agreed by consensus to protect the entire Dalbergia genus under Appendix II in order to close the enforcement loophole and to protect rosewood from extinction. This greatly facilitates effective enforcement of trade and forestry laws, and marks one of the most ambitious global agreements on international timber regulation to date. This landmark decision is accompanied by growing interest in emerging technologies that make identification of timber species faster and more affordable, which can aid authorities in the implementation and enforcement of CITES regulations.

Rosewood is one of the largest forestry challenges today. Rosewood demands legislation, strict enforcement, and a universal agreement to stand up to the illegal timber trade before it’s too late. The new regulation is a significant move towards reducing destructive illegal logging and international wildlife trafficking that harms forests and forest communities. But it is also monumental for the guitar industry, which will now have to provide CITES permits for all commercial trade, imports, and exports of rosewood guitars.

Legal language on “non-commercial personal use” protects traveling musicians from officials seizing their precious instruments, but the new CITES listing marks a new era for instrument manufacturers.

In my research on tone woods I ran into many opinions about the importance and diversity of tone woods, in relation to the price of the final product. One controversial story, penned down for Guitarnation.com by luthier/instrument maker John Calkin intrigued me, as he claims that “the sound of an instrument is in the hands of the maker, not in the wood.” A conversation that re-enforces that instrument pricing is sharply influenced by brandname marketing. Your opinion would be welcomed in a comment.

Previously in this series of Six Tonewoods we presented:

Other interesting stories on green harvesting and re-cycling of tone woods:

https://web.archive.org/web/20110503050132/http://www.hvgb.net:80/~tonewood/servicepage.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tonewood